One in 100 deaths worldwide is by suicide, and while the overall rate is falling, it is rising in the Americas. Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, according to a report titled “Suicide worldwide in 2019,” with data before the COVID-19 pandemic, said the global health body, which wants to combat the trend. “Every year, more people die as a result of suicide than HIV, malaria or breast cancer – or war and homicide,” said the WHO.

In 2019, the latest figures available, more than 700,000 people died by suicide – one in every 100 deaths – prompting the WHO to produce new guidance to help countries improve suicide prevention and care. “We cannot – and must not – ignore suicide,” said Tedros Ghebreyesus, the WHO director-general. “Our attention to suicide prevention is even more important now, after many months living with the COVID-19 pandemic, with many of the risk factors for suicide – job loss, financial stress and social isolation – still very much present.”

New data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that suicide deaths between 2019 and 2020 decreased by 3% overall (by 2% in males and by 8% in females). However, suicide deaths for males in three age groups (10–14 years, 15–24 years, and 25–34 years) increased. And while suicide deaths decreased amongst white and Asian males, deaths increased for Black, American Indian and Alaskan Native, and Hispanic males.

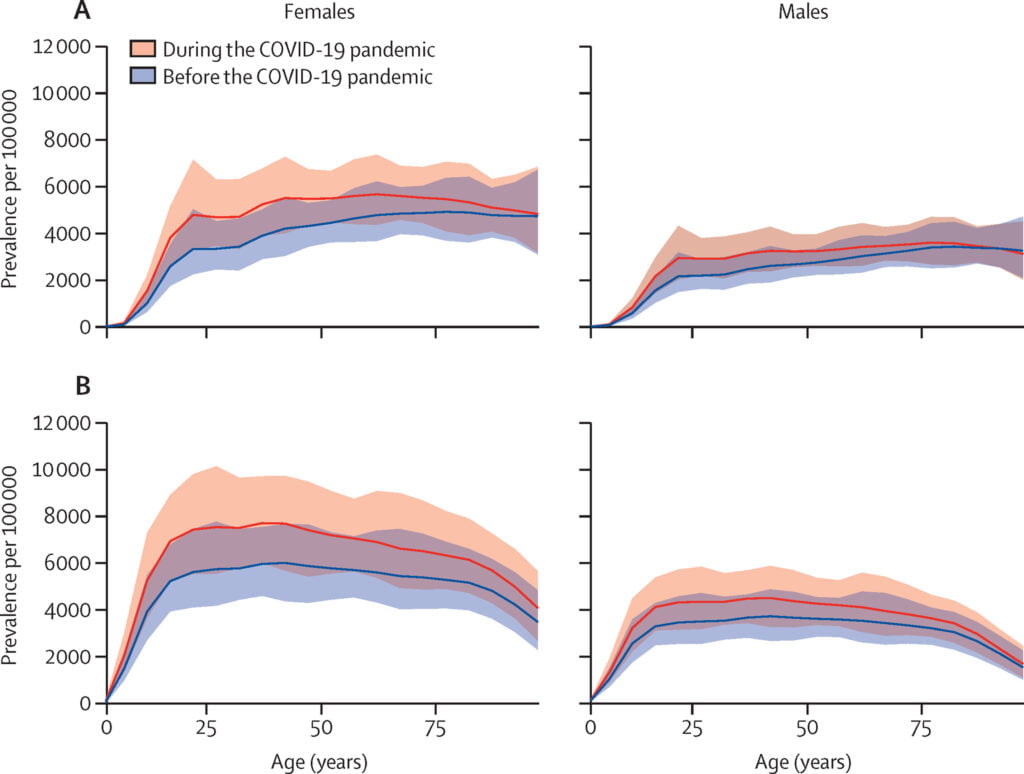

Although we don’t know exactly what has led to the overall reported declines and increases in suicide rates, experts believe the COVID-19 pandemic may have played a part. “It’s been clear throughout the pandemic that the overall impact on the population’s mental health has been significant,” says Christine Moutier, MD, Chief Medical Officer at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). During the pandemic, about 4 in 10 adults in the US have reported symptoms of anxiety or depression, compared to one in 10 adults who reported between January and June 2019. “Experiences such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts have been more prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for youth and young adults, caregivers, frontline workers, and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) populations,” says Dr. Moutier.

Picture at https://www.thelancet.com

But when it comes to suicide death rates, the situation is complex. “Suicide rates are greatly impacted during times of national tragedies or major world events,” says Julian Lagoy, MD, a psychiatrist with Community Psychiatry and MindPath Care Centers. For instance, four years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City analyses of death records showed there was no increase in suicide rates. “This may be because there was a general sense among the population of ‘we are all in this together,’ “ Dr. Lagoy says. Dr. Moutier adds that even when distress is high, suicide isn’t a foregone conclusion, because help seeking can also rise, and during periods of community-wide distress, cohesion and interpersonal connectedness increase, which can mitigate against suicide risk. She also stresses that it’s important to understand that COVID-19 and associated mitigation efforts such as physical distancing alone don’t cause suicide.