Peacemaker Fellowship

Violence prevention has been a priority among health officials for decades and a number of intervention programs have been established. Strategies to address violent crime may require a thorough investigation of its root causes to determine the best route of intervention.

In 2010 , when the city’s homicide rate was soaring, city workers offered Richmond’s most dangerous players training and support to stay out of trouble. Specifically, Operation Peacemaker (formally Peacemaker Fellowship) provides job training, substance abuse treatment, mentorship and up to a thousand bucks a month if individuals put away their guns.

DeVone Boggan, the program’s creator, said private grants pay for the stipends. Boggan started the program after analyzing city crime data. He discovered that a small percentage of the population committed most of the shootings. By singling out about 30 ring leaders Boggan believed he could have the greatest effect on reducing gun violence.

The project, which started in June 2010, aims to reduce homicides and help potential killers in many areas such as education, employment, parenting, financial management, medical help, behavioral help, anger management, conflict resolution, personal safety, spirituality and recreation.”

The very first step of the process is hiring a group of street outreach workers called Neighborhood Change Agents.

Subsequently, agents who know the local environment very well contact potential killers and try to convince them to sign up for an 18-month fellowship.

After six months in the program, young participants are eligible for a scholarship of $ 1,000 a month for 9 of the remaining 12 months. “The stipend is a gesture of saying you are valuable, your expertise is valuable, your contribution to this work of creating a healthier city is valuable,” DeVone Boggan told KQED in 2016. He said private grants pay for the stipends.

The program includes feeding homeless people, working with elderly, talking to other young kids and parents who have lost their children to gun violence.

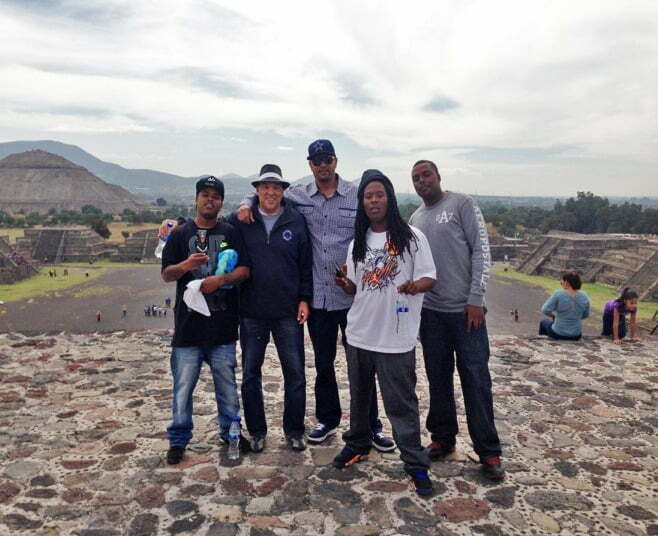

In addition to the scholarship, fellows also have an opportunity to travel. They can travel outside the country with rivals who joined the same program. According to Devone Boggan, leader of the project, traveling can not only broaden their horizons, but also show them that their peers are very similar.

Photo: Richmond Office of Neighborhood Safety

Authors of the program try to help fellows also with social assistance and job. They seek to understand needs and interests of participants and try to work and live a decent, productive life.

According to supporters of the program, this procedure can be applied elsewhere. The condition is that each city must agree to 3-5-year commitment. The cost is $250,000 a year and the rest will be funded through nonprofits.

Some criticize that the program doesn’t deal with prison re-entry programs and focus only on reducing gun violence, not reflecting the complexity of the problem.

One of the key factors is communication between the offenders’ relatives and the police. Parents may inform police of their sons´ illegal firearms if police will agree to seize them – at possibly considerable trouble and cost to their possessors – without pursuing charges.

All these sorts of possibilities rest on the exchange of information between authorities and others. (Scott Decker and Richard Rosenfeld, Reducing Gun Violence: The St. Louis Consent-to-Search Program)

Impact

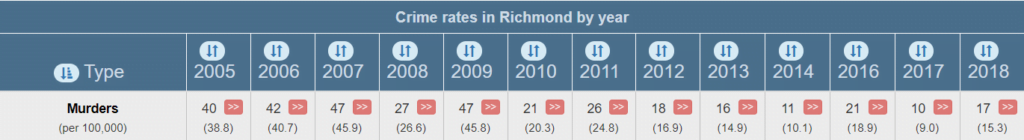

Between 2007 and 2014 Richmond experienced a 76% reduction in homicides. In 2013, Richmond recorded 16 murders, the lowest number it had seen in 33 years. Comparing a decade (2003 – 2013), all crimes fell by 40 percent. In 2017 there were only 10 murders in Richmond.

The program has graduated three groups of fellows, ages 14-25. About one fifth (21%) were victims of gun violence prior to participating. Of the 68 fellows who have completed the program, 94% remain alive and 84% have not been injured by gun violence since becoming a fellow. In addition, 79% have not been suspects in a new firearm crime since becoming a fellow.

There were only 16 murders in Richmond in 2019, confirming the positive trend.

There’s early evidence that local violence prevention strategies were a “key change” contributing to these huge decreases. It includes a refocused, more community-driven “Ceasefire” policing strategy, and intensive support programs that do not involve law enforcement.

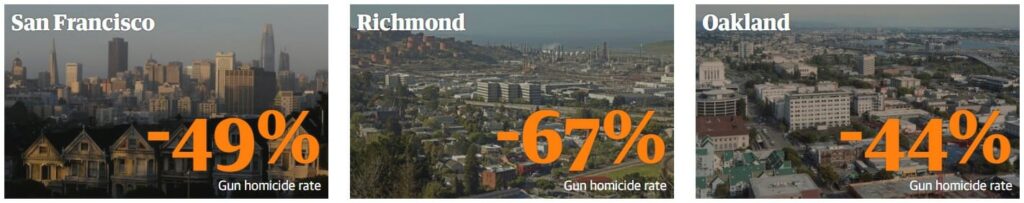

Gun homicide rates for all races have fallen, but the drop was largest for black Bay Area residents: a 40% decrease. (SF -49%, Richmond -67%, Oakland -44%)

The key factor was a daily contact with potential killers. Program leader Devone Boggan believes that young people realize they are living a lie and their opponents are very similar to them. And that is important to realize before pulling the trigger.

A study, published in the American Journal of Public Health, finds gunshot wounds and killings have fallen by 55% since the fellowship program began.

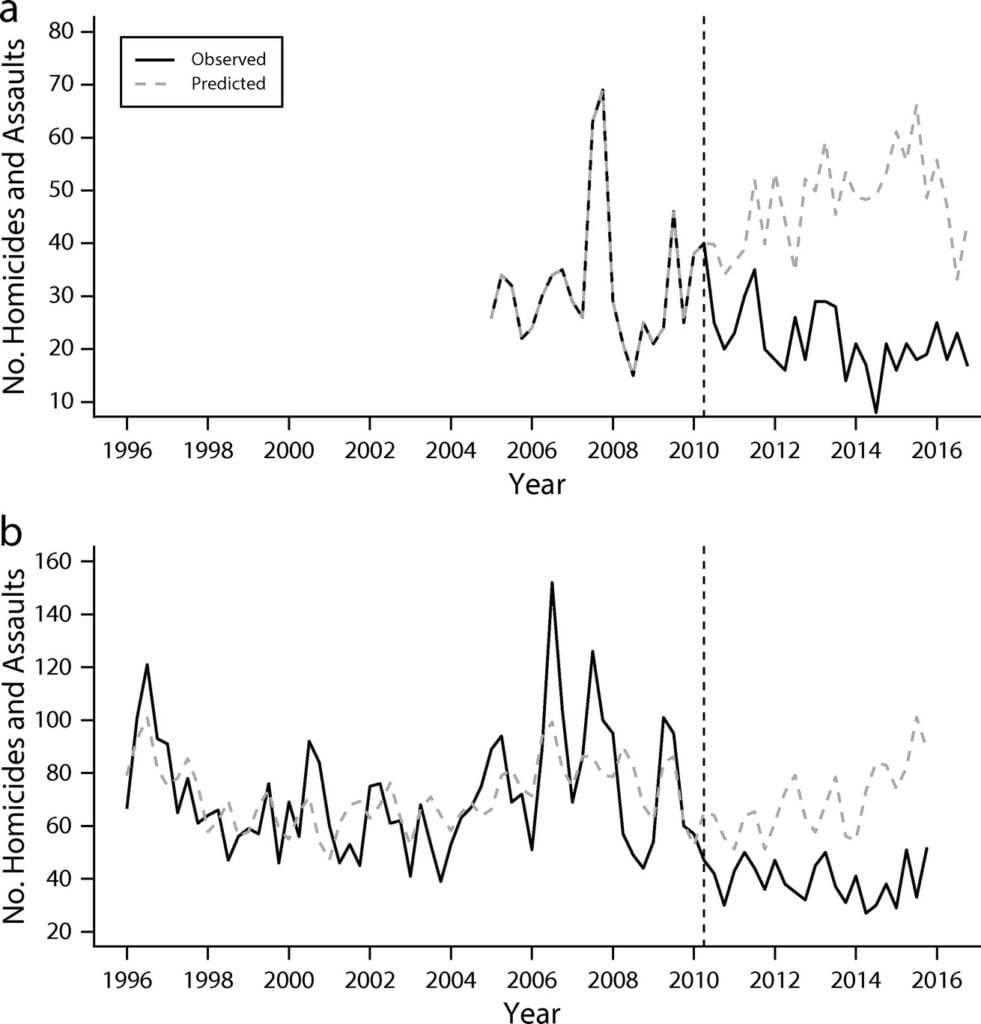

Observed and Predicted Firearm Homicides and Assaults Before and After Peacemaker Fellowship

(a – health data, b – crime data)

The program was associated with reductions in firearm violence (annually, 55% fewer deaths and hospital visits, 43% fewer crimes) but also unexpected increases in nonfirearm violence (annually, 16% more deaths and hospital visits, 3% more crimes).

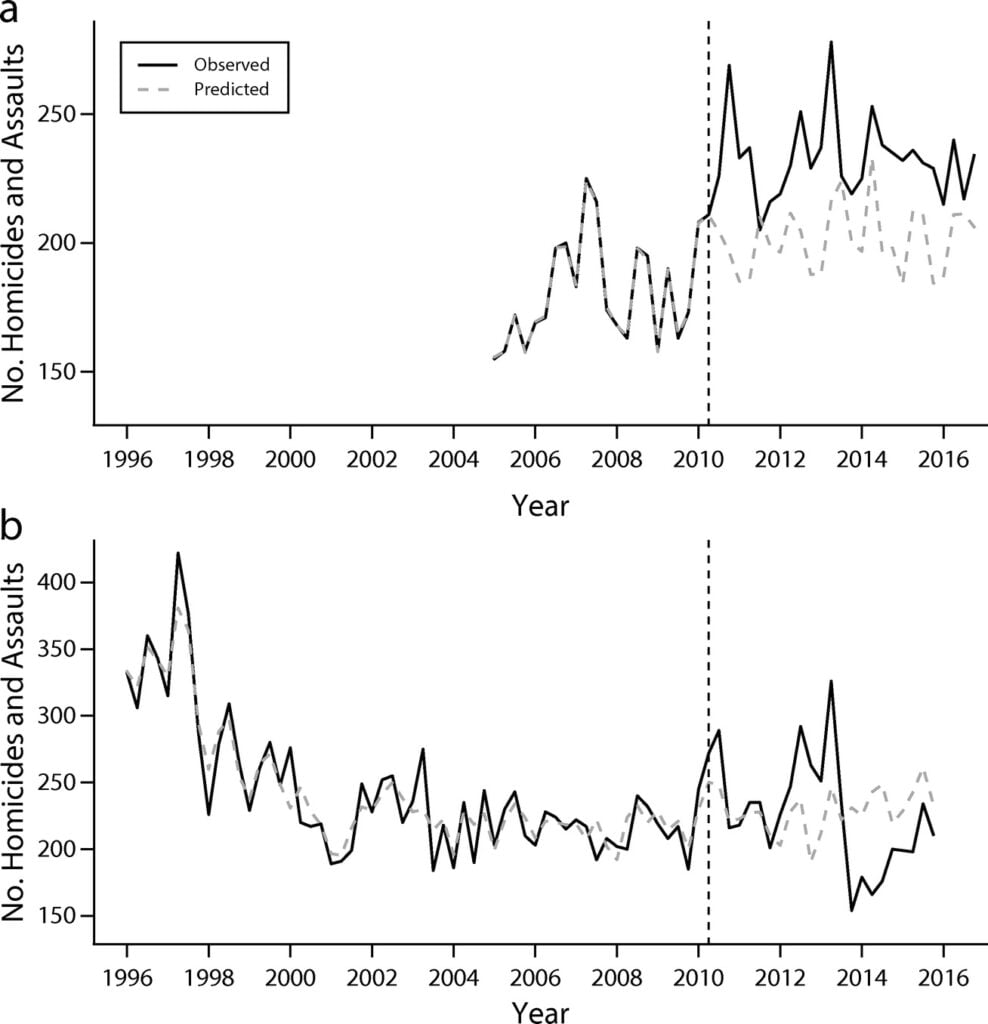

These associations were unlikely to be attributable to chance for all outcomes except nonfirearm homicides and assaults in crime data. Jennifer Ahern, a UC Berkeley epidemiologist, praises the multi-pronged approach, even as she warns of unintended consequences. “The unexpected finding was a small increase in non-firearm related violence like being punched, or being kicked or perhaps a knife might be involved.”

Observed and Predicted Nonfirearm Homicides and Assaults Before and After Peacemaker Fellowship

(a – health data, b – crime data)

Jennifer Ahern teoretizes the 16 percent rise in beatings and stabbings may be happening because gang members are working out conflicts through other means than guns. Or, the uptick may result from changing power dynamics on the streets. “As the program is rolled out in new cities we think it’s important for them to keep an eye out for other forms of violence,” Ahern says. “It’s possible violence may shift in how it’s carried out.”

However, Ahern says her cautionary note is not meant to undermine the program’s success. As Richmond’s gun violence plummets, the fellows are thriving. Of the 106 fellows who have participated, 85 have not had a firearm-related injury, and 74 are not suspects in a firearm-related crime. And the true highlight: 101 of the 106 young men are alive.

Experts admit the positive impact of the program but add that decrease in homicides is also the result of better policing, neighborhood involvement, gun laws enacted in California since the 1990s and an overall drop in homicide rates across the country. It is impossible name exactly the success factors, but one thing is clear. Some fellows found a job (construction, city services, recreation, youth development, food services, retail) and have a possibility to live full-value productive life.

It may be impossible to pinpoint exactly what factors are driving the changes in the Bay Area, experts say. Violence is complex, shaped by a multitude of elements and dynamics. But some wider trends are clear. The Bay Area’s drop-in gun violence does not reflect a drop in overall “crime”. The rate of property crimes such as theft and burglary have decreased only 16% across the region as gun violence has fallen by nearly a third. San Francisco has seen its property crime rate increase even as the number of people killed in gun homicides has dropped. (The Guardian)