The Housing First system was developed in 1988 in Los Angeles and then spread to other cities. The idea is to help homeless people to move from shelters through transitional housing into own permanent housing.

Study by Dennis Culhane which examined the period 2004 – 2010 found that prevention services were most effective for the households – both family and single adult – who were at the highest risk of becoming homeless, rather than the households who fit prevention programs´ eligibility criteria. It means, that successful strategies for homelessness prevention must efficiently target people at greatest risk for experiencing homelessness.”

Following a period when homelessness rose in many countries, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted governments across the OECD area to provide unprecedented public support – including to the homeless. In the United Kingdom, for instance, people who had been living on the streets or in shelters were housed in individual accommodations in a matter of days. And in cities and towns across the OECD, public authorities worked closely with service providers and other partners to provide support to the homeless that had previously been considered impossible.

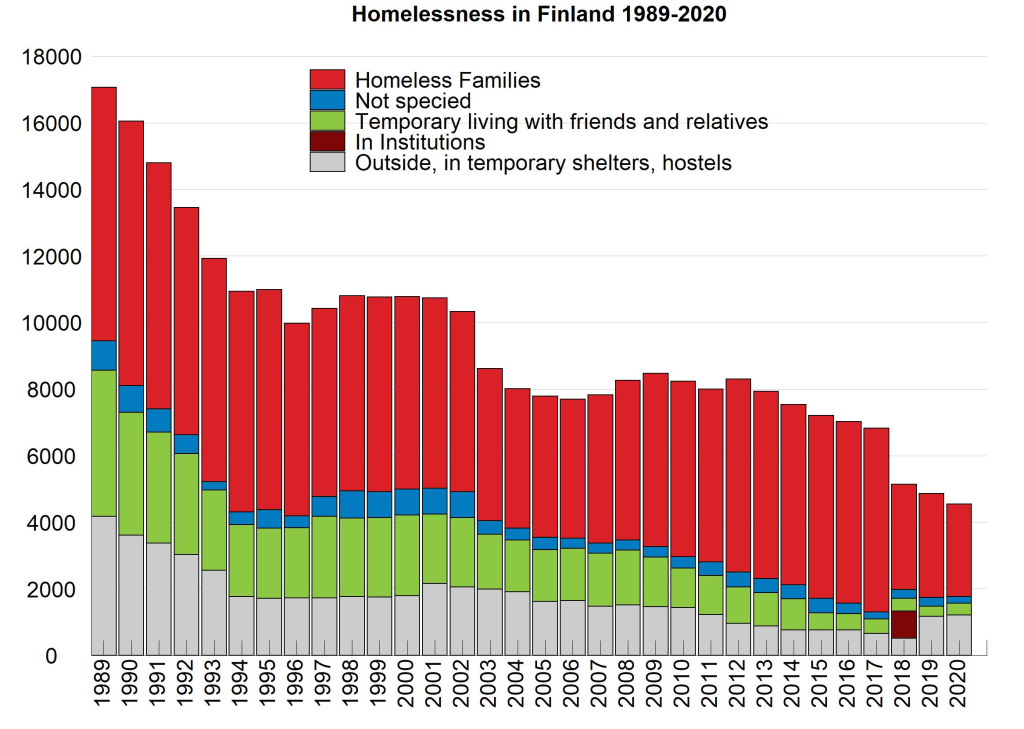

How can countries build on this momentum and ensure more durable outcomes? The experience of Finland over the past several decades – during which the country has nearly eradicated homelessness – provides a glimpse of what can be possible with a sustained national strategy and enduring political will. The number of homeless people in Finland has continuously decreased over the past three decades from over 16 000 in 1989 to around 4 000, or 0.08% of the population. This is a very low number, especially considering that Finland uses a relatively broad definition of homelessness, whereby in particular it includes people temporarily living with friends and relatives in its official homelessness count. In 2020, practically no-one was sleeping rough on a given night in Finland.

This is undoubtedly a remarkable success, even if comparing homelessness statistics across countries is fraught with difficulties (OECD, 2020). Many homeless people live precariously, with the implication that statistical tools such as household surveys typically fail to accurately measure their living conditions. Furthermore, countries define homelessness very differently, for instance counting people who temporarily live with friends or relatives as homeless (as Finland does) or excluding them from homelessness statistics. While there is no OECD-wide average against which to compare Finland’s homeless rate of 0.08%, other countries with similarly broad definitions of homelessness provide points of reference, such as neighbouring Sweden (0.33%) or the Netherlands (0.23%).

Finland’s success is not a matter of luck or the outcome of “quick fixes.” Rather, it is the result of a sustained, well-resourced national strategy, driven by a “Housing First” approach, which provides people experiencing homelessness with immediate, independent, permanent housing, rather than temporary accommodation (OECD, 2020). A key pillar of this effort has been to combine emergency assistance with the supply of rentals to host previously homeless people, either by converting some existing shelters into residential buildings with independent apartments (Kaakinen, 2019) or by building new flats by a government agency (ARA, 2021). Building flats is key: otherwise, especially if housing supply is particularly rigid, the funding of rentals can risk driving up rents (OECD, 2021a), thus reducing the “bang for the buck” of public spending.