Focused deterrence was originally developed by David Kennedy, one of the most popular criminologists in the US. In the mid-1990s he helped Boston’s authorities to apply effective approach to eliminate youth gun violence.

Methodology reminds a system of “good and bad cop”. Police target a small group of chronic offenders (often gang members) and offer them two options – to live a decent life with various forms of state assistance (jobs, education, social services) or punishment including jail if they don’t stop.

David Kennedy with colleagues, city officials, community leaders and outreach workers created “call-in” system. It’s a kind of face-to-face meeting, where they are informed about new highly effective state focus to strictly eliminate a gun violence. The meeting also includes a moral message against violence.

Law enforcement, community members, and service providers delivered an unified message to dealers: “we care deeply about you, we will help you, but you are hurting people and destroying the community and you need to stop…you could be in jail tonight”. During that show them evidence but try to deliver message “a way to step back without losing face.” (David M. Kennedy, Deterrence and Crime Prevention)

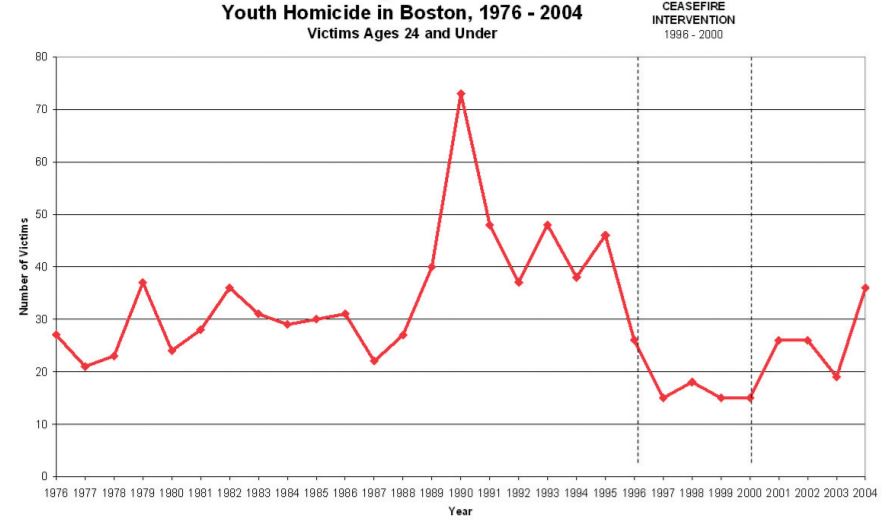

The immediate result of Operation Ceasefire was a 63 percent reduction in youth homicide and a 30 percent reduction in homicide citywide, what has been called the “Boston Miracle.“ (Braga, Anthony A., Weisburd, David L., The Effects of “Pulling Levers” Focused Deterrence Strategies on Crime”)

Youth homicides in Boston stopped completely for 17 months and the overall homicide rate fell by nearly one-half. Youth violence in the city fell by two-thirds in the two years after Ceasefire, and homicide amongst all ages by a half. There were around 100 homicides before operation Ceasefire. By 1999 it was 31.

An academic study of gun violence in Oakland neighborhoods found that the city’s focused deterrence strategy, known as “Ceasefire”, significantly reduced shootings, even when accounting for the level of gentrification in different areas.

The core insights of traditional deterrence theory remain useful. Sanctions may be formal (arrest) or informal (job loss). Informal sanctions may be internal (guilt and shame) or external (losing a girlfriend). To offender, the prospect of a long federal drug sentence may carry little deterrent weight. He may, on the other hand, care deeply about his grandmother´s disapproval. (David M. Kennedy, Deterrence and Crime Prevention)

Several studies confirmed the impact of significant others, conscience, embarrassment and shame to be a powerful deterrent to tax offending, drunk driving, and petty theft; for the first two offenses, shame was a stronger deterrent than the threat of legal sanction. (Grasmick and Bursik, Conscience, Significant Others, and Rational Choice: Extending the Deterrence Model)

Lack of communication is considered by experts as one of the biggest mistakes. This is an extremely simple, but profoundly significant, point. Offenders regularly face exposure to legal sanctions of which they are unaware. What is not known cannot, in theory or in practice, deter. Informing them satisfies the theoretical need and may make a difference in practice. (David M. Kennedy, Deterrence and Crime Prevention)

The communication of sanction risk is crucial to deterrence not only in the United States. It has been proved that the key success factor of twenty-one English burglary-prevention projects was publicity about the projects. (Shane D Johnson and Kate J. Bowers, Opportunity is in the eye of the Beholder: The Role of Publicity in Crime Prevention)

Communication really works what also demonstrates the following example. One gang member´s girlfriend said withholding sex was proving a powerful incentive. “The boys listen to us. When we close ourselves off a bit, they listen to us. If they don’t give up their weapons, then we won´t be with them,” Margarita told AP Television. “They say that if we don’t drop our weapons, they won´t be with us anymore. We need our women, and you ´ll change for your woman,” said a local gang member, who called himself Caleno.” (David M. Kennedy, Deterrence and Crime Prevention)

Avoiding mistakes like false promises by authorities, misinformation of potential offenders, and failure of enforcement strategies is the key to by successful in facing homicides.

Focused deterrence is possible successfully use against various kinds of crimes such as domestic violence, homicides, gang killings or drugs.

High Point Project

After successfully applying this strategy against drug dealers in 2002, High Point decided to use the same approach to eliminate domestic violence.

In 2009, a major meeting took a place in the presence of the police and another 25 agencies including advocate groups and attorney´s offices. The outcome of the meeting was common agreement of using focused deterrence against chronic abusers.

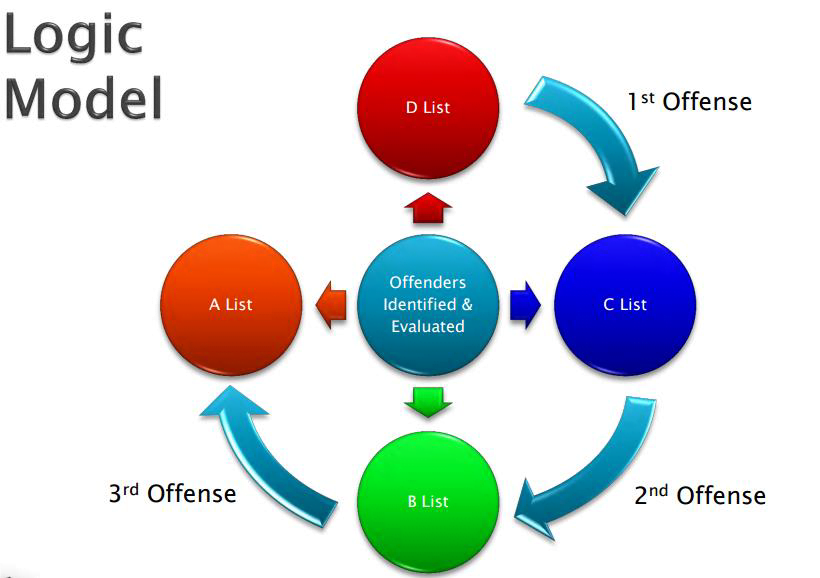

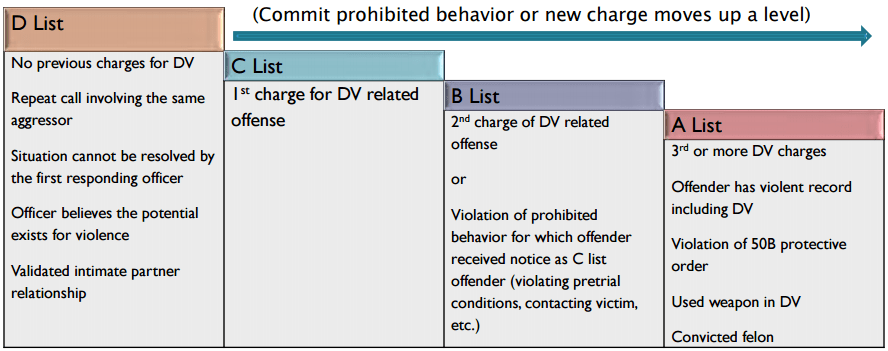

In cooperation with community, High Point police department created a four-tier system. The idea is pretty simple. According to behavior, abusers are classified into four categories (A, B, C, D) from the least dangerous (D) to the most dangerous individuals (A). The strategy also includes a comprehensive protection of victims, depending on the category of offender.

Following a D-list offense, the victim receives a letter detailing available services; a C-list offense is followed by in-person victim outreach to offer services; when B-list offenders are called in, social services and victims’ advocates make direct contact with associated victims to ensure victim safety and get feedback on offender’s post-call-in behavior; and A-list offenses are followed by direct outreach by victims’ advocates to offer all available support and safety planning structures.

According to criminologist David M. Kennedy, the program focuses on six key points:

- Protect women from the most dangerous abusers.

- Address the abusers (both by written communication and face-to-face meetings with law enforcement and community partners).

- Focus on deterrence and outreach to abusers.

- Have abusers learn from other offender experiences (including swift punishment for most violent abusers).

- Get the abusers to take advantage of the opportunities offered through the initiative.

- Prevent putting women at additional risk.

- The police department place a great emphasis on the protection of victims (working with all interested parties) and provide significant assistance to the abusers (e.g. help earning their General Educational Development).

Impact

To avoid the nightmare scenario (after receiving the message abuser kills the victim), the task force created safety plans for these and other at-risk women living with abusive partners. The women were asked to identify someone that advocates could call — a colleague at work, a neighbor, a family member — who would know if the victims were all right even if the service providers couldn’t reach them directly. No one knew if these measures would be enough.

IPV homicides have dropped dramatically in many ways – victim injuries, calls to police recidivism.

There were only two in the seven-plus years since project started (2009 to year-to-date 2016). The first was arguably not IPV – an honor killing within a recent immigrant family – and the second was IPV within a couple passing through the city and staying in a local motel.

There were 17 intimate partner homicides in the five years prior to implementation (2004 to 2008) and only 11 in the next 11 years (2009 – 2019). In 2019, they recorded only 2 intimate partner homicides.

Recidivism for domestic abuse declined significantly too. Twelve months into the program, only 9 percent of listed offenders in High Point had attacked again, compared with 20 to 34 percent of abusers nationwide. Indeed, recidivism rates are so low that High Point hasn’t had to schedule a call-in for B-class offenders since September 2014.

In the years 2011 – 2014, victim injuries decreased from 66.8 percent of incidents to 47,3 percent.

Police across the country carry mandatory arrest on suspicion of domestic violence. Interested parties have improved the risk assessment system. Community members also developed social services structure. Mandatory consultations for offenders have become ordinary.

Calls for service reduced by 20 percent over 3 years.

From when the program started in April 2012 until August 2019, High Point Police have put around 3,000 people on the list. Around 18.4% total have gone on to commit another act of domestic violence. 57 people are considered ‘A’ list offenders, and 8 have them have committed another act, which is a 14% recidivism rate. The program has put over 3,500 offenders on notice in seven years.

High Point had been applying focused deterrence for over 15 years and effectively addressing individual violent offenders, group violence, overt drug markets, and other serious crimes.